Jason Crawford asks, “What’s the crux between EA and progress studies?” This series of posts will be my strike at the question from a few different angles.

There’s a number of new, online movements that are very interested in improving the modern world. I’m particularly interested and connected to two of them: Progress and Effective Altruism. I founded and serve as an editor for Works in Progress, where we seek to elevate important ideas for the future. In college, I founded the Brown University Effective Altruism chapter. I’d like to develop a more clear understanding of how the two movements relate to each other, pragmatically and philosophically, over a short series of posts.

I want to start by making a distinction: When Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen first wrote about progress studies, they called for an interdisciplinary academic movement. This meant opening up a discussion between different academics working on issues related to progress (like economic historians, developmental economists, and management scientists) to put together a more complete “science of progress.”

Since then, there’s been enough popular interest in their idea to merit a larger mandate. We have a large pool of talent and capital that’s invested in the goal of accelerating progress (As Cowen and Collison wrote, "Progress Studies is closer to medicine than biology: The goal is to treat, not merely to understand."). When I write about “Progress” and “the Progress Community,” I’m going to be referring to this larger umbrella, rather than just people interested in doing “progress studies'' in the academic sense.

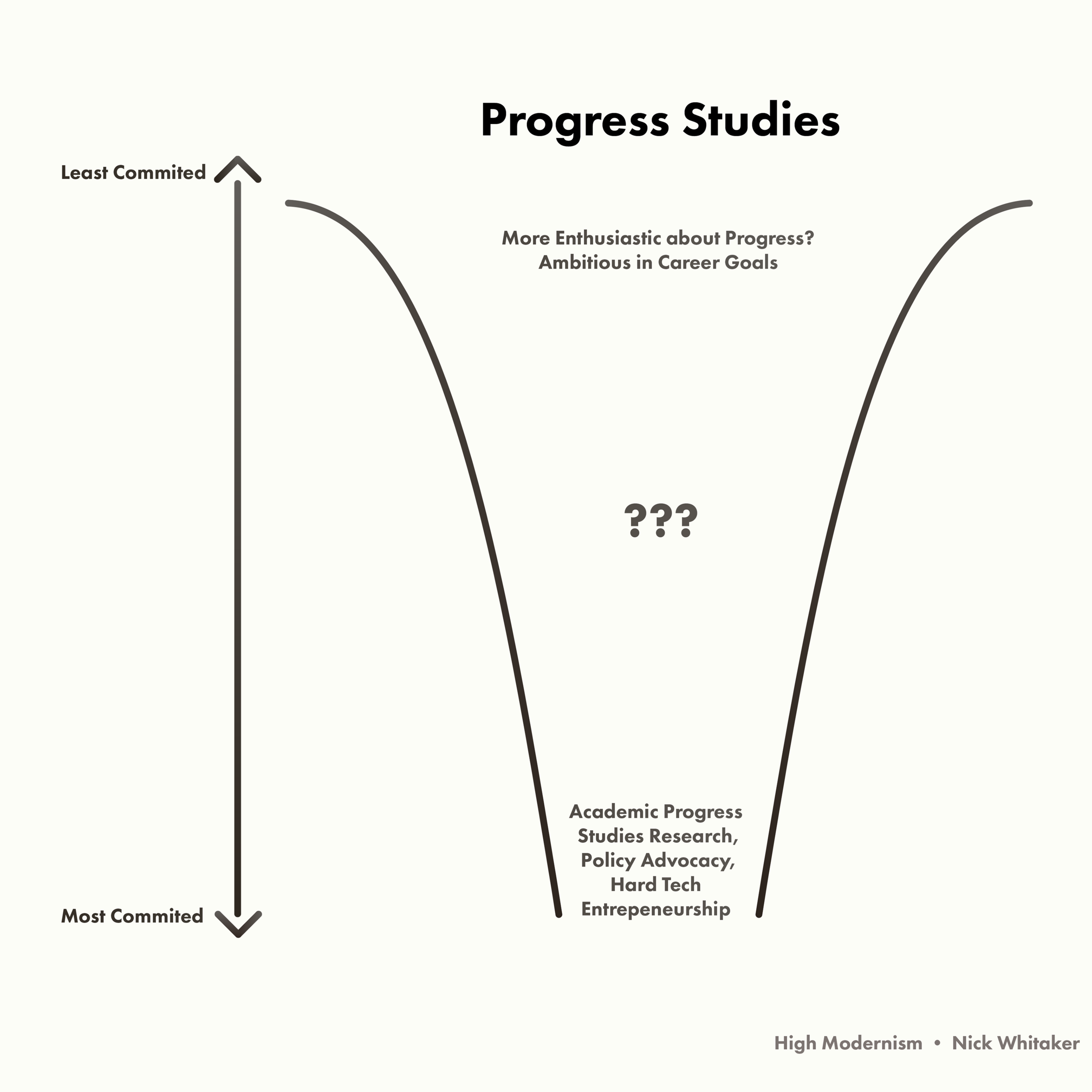

With that in mind, here’s a general picture of what the current Progress Community landscape might look like:

It’s with this understanding that we can begin to compare Progress to EA.

Let’s start by looking at each’s actions. Both movements are interested in creating a community and directing that community towards certain ends. In Effective Altruism, it’s relatively clear what that community and direction look like.

At the top of the funnel, a person might move some of their regular donations to a Givewell charity. In the middle, a person might have taken the Giving What We Can pledge, done 80,000 Hours career consulting, and maybe pursued an EA bent to their work, or perhaps is involved with their local EA chapter doing community building. At the bottom of the funnel, a person might be working full time in an EA organization or is doing serious earning-to-give.

To be clear, this has changed since EA began. In the early days, the movement was much more focused on earning-to-give and donating to global health charities. Since then (and since the involvement of a number of large donors), EA has become more focused on directing talent to found and staff EA organizations and projects, and most of those new organizations and projects are longtermist. But the EA community has always been able to direct their talent.

Now let’s look at Progress:

I don’t mean to be too pessimistic here: there’s a lot of great projects taking place under the Progress umbrella, and a number of even more exciting projects to be announced in the next few months. But the number of people involved full-time with these projects is likely less than 20. We have largely failed at mobilizing the talent and resources we have at the top and middle of the pipeline in the way that EA did even as an incipient movement. EA could immediately say, “Earn to give and donate to Givewell,” while Progress has no such analogue. “Celebrate progress”?

This is all the more disappointing when we consider how well the Progress community has done in getting interesting ideas into the popular discourse. There are at least half of a dozen high quality blogs and Substacks devoted to progress, and the larger economics and rationality blogosphere routinely engages with it, not to mention major publications. This is one area where Progress has markedly outperformed EA so far. But if Progress is to be “more like medicine than biology,” we need to be converting that intellectual enthusiasm into real world action and change.

In terms of actions, the “crux” between EA and Progress might mean, “At a given level of involvement, which track would be more worthwhile?” If you’re a highly skilled, charismatic engineer who wants to be fully committed to one movement in the other, it’s a legitimately difficult question of whether you should try to start a world changing company or do AI safety research. But at the top and middle of the funnel, it isn’t exactly clear what decision you would be making, and whether there is any conflict between the two movements at all.

So what should Progress be allocating talent towards, beyond its academic questions? The obvious thing would be fast-growing companies. And to a certain extent, Progress as a movement has seemed to be center-left people in tech learning to stop worrying and love capitalism, rediscovering the power of free markets as an engine of growth and the virtue of the entrepreneur (and hardworking employee) in driving growth forward. It’s moral permission to be a proud capitalist.

All of that is good and correct. Indeed, it is a core message of Tyler Cowen’s Stubborn Attachments. But even if Cowen is right, that the “common sense morality” of working hard and providing for your loved ones is a reasonable approximation of true morality, that goal alone can’t do justice to the potential of Progress as a movement. For one, it’s not in our comparative advantage to push that line, as it’s already pushed by Standard American Values, religious institutions, etc. We also don’t need a movement to push people to work at fast growing start ups, as we already have stock options to do that. There might be a place to help with the amount of talented new grads that go into consulting and banking relative to tech, but this seems more to do with a skills mismatch created in higher education than something a movement is equipped to solve.

A better idea for the Progress Community would be to coordinate people to solve problems, both technological and political, that usually would be intractable but for an unusual coordination of talent and capital. All founders do this coordination to some degree: they identify a problem that people have been unable to solve and coordinate resources to solve it. Especially good founders like Elon Musk are able to coordinate talent and capital to solve problems further afield, by coordinating even more talent and more capital. Progress as a movement and network could do some of the founder’s work for them, like getting all the engineers and VCs that want to work on flying cars in one place. We could convince people to raise their ambitions and career trajectories, identify far-afield, important problems, and then get people invested in actually solving them. In fact, this is sort of like what EA looks like at the moment.

The political case may be even more interesting. There’s a number of political and societal problems that aren’t being solved despite everyone agreeing that they are big problems. Just like tech, it will take talent, capital, and an organizing force to solve these problems. So we could also do things like get all the people and donors that want to fix housing or transit together.

In either case, the Progress community could begin by inspiring people to be more ambitious, create a Schelling Point for ambitious people to lower the cost of search and coordination, and identify people to do academic progress studies research, lead pro-progress policy advocacy, and found world changing companies. In both the technological and political case, the Progress community could become a place for definite optimism rather than indefinite optimism. I will return to these ideas for a mature Progress community in a future post.

But for now, any comparison between the EA and Progress communities needs to begin with this massive discrepancy in action and direction. Progress advocates can’t credibly tell EAs to be more like them until what that is can be better defined in their actions. At the same time, EAs can say that they will be the real vehicle of progress. Should the Progress Community agree with them? Should progress simply be a subcategory in EA longtermism?

These questions get into the two groups' thinking, which we will address next time.